“The catch-all phrase for improving the human condition may need rephrasing.” – Richard Dion

Photo Credit: Indiegogo

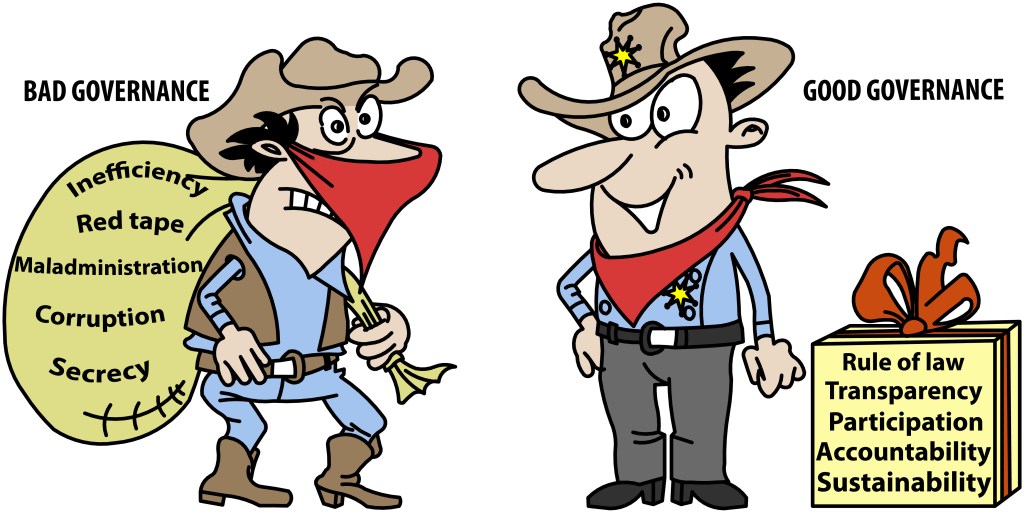

For the last few decades, “good governance” in the development context has been a catch-all phrase for improving not only a state’s processes but by implication leading to improvement in the lives of its citizens.

Despite that goal, the phrase, which helped to frame an important aspect of the development agenda, is too general, has an element of arrogance and attempts to signify so much that it means too little.

All good?

Good governance may have been a victim of marketing – short, sharp and with consonance. The phrase has worked in the development community, particularly in English, and in receiving governments, but that time may be past.

As an adjective, “good” is far too subjective, with interpretation from a donor usually dramatically different from that of the receiver. What’s the baseline? Is there a baseline? What does “victory” look like or the “outcome” resemble? As a phrase, good governance has little “SMART” (specific, measurable, assignable, realistic, time-bound) indication built into it.

Consulting in natural resource governance, I was and continue to be surprised that ‚good governance‘ is not perceived in a derogatory fashion in resource-rich and at times governance poor countries. A programme concentrates on good governance, so the country may / must have bad governance. One possible explanation is that the phrase is positive. However, given the current reevaluation of race relations sweeping the United States and indeed the world, it may be even urgent to consider a new term.

For example, one of the reasons why Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index is so hotly contested in many countries is that a spade is called a spade – this land is perceived to have a corruption problem. The ensuing press headlines (and those tasteless jokes) about “corruption” fan the flames and lead to many countries either doubting the methodology or simply ignoring it all together, resulting in little or no real policy action on the ground. There is a potential risk that a well-meaning exercise remains just that – an exercise. Therein lies the real tragedy.

Flipping it around to a “governance index”, with the equivalent ranking, is perceived far more diplomatic, more palpable on the receiving end and would likely lead to more traction within a country. To continue the thought, the World Bank’s “Ease of Doing Business” is really just “Difficulty of Doing Business”. However many countries will be trying intensively to improve their ranking. I don’t believe that they would be so enthusiastic if they were perceived as difficult.

Going from “good” to “bad” won’t be helpful, so sideways may be the best option.

Photo Credit: Bocawatch

The case for “accountable governance”

Accountability is to see results. At its core, development assistance is to see results, make a difference, point to something tangible.

In this respect, “accountable governance” is perhaps closer than “good governance” to what donor countries intend when they offer support to recipient countries to improve the lives of the population.

Donor countries should make it very clear to recipient countries what outcomes are expected and in which time period. Receiving countries would be under no illusions that the goal is accountability. The needle is moving in the right direction with Germany’s Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development announcing their 2030 strategy at the end of April which will move away from the “watering can” approach and move towards indicators around good governance, observing human rights and fighting corruption. It’s early days – it will be interesting to see how public those indicators are in the coming years.

Photo Credit: AllAfrica.com

Pegging accountable governance to indices

To make accountable governance work, a results-oriented approach must be its backbone, with the increasing diversity of governance indices handy. Whether it’s the Ibrahim Index of African Governance, Bertelsmann Transformation Index, the Berggruen Governance Index, the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s Resource Governance Index or TI’s Corruption Perceptions Index, both provider and receiver of development assistance should make it clear that the environment has evolved.

Very often, governance indices do not even register in the country which has been graded. Occasionally, this has to do with the very basic issue of translation. At the very least, governance rankings could be sent to the ambassadors of key donor countries for onward presentation with key government officials. With the millions of dollars and the thousands of hours being invested in the process, all institutions should be sparing thousands of dollars for translation.

A new tone for take-up

To help resolve the challenge of accountable governance, it is crucial that the tone is measured, that the offer of assistance is genuine and that there are no more moving goalposts. In such instances, the receiving country will likely be considerably more open to criticism and the attempts to create a realistic path to reform much more productive. If donor countries want uptake, the tone needs to be right. With that, a real dialogue, not debate, about the challenges and opportunities can take place, ensuring that governance moves beyond good and becomes accountable.

Richard Dion is a consultant in governance, communications and regional development based in Germany.