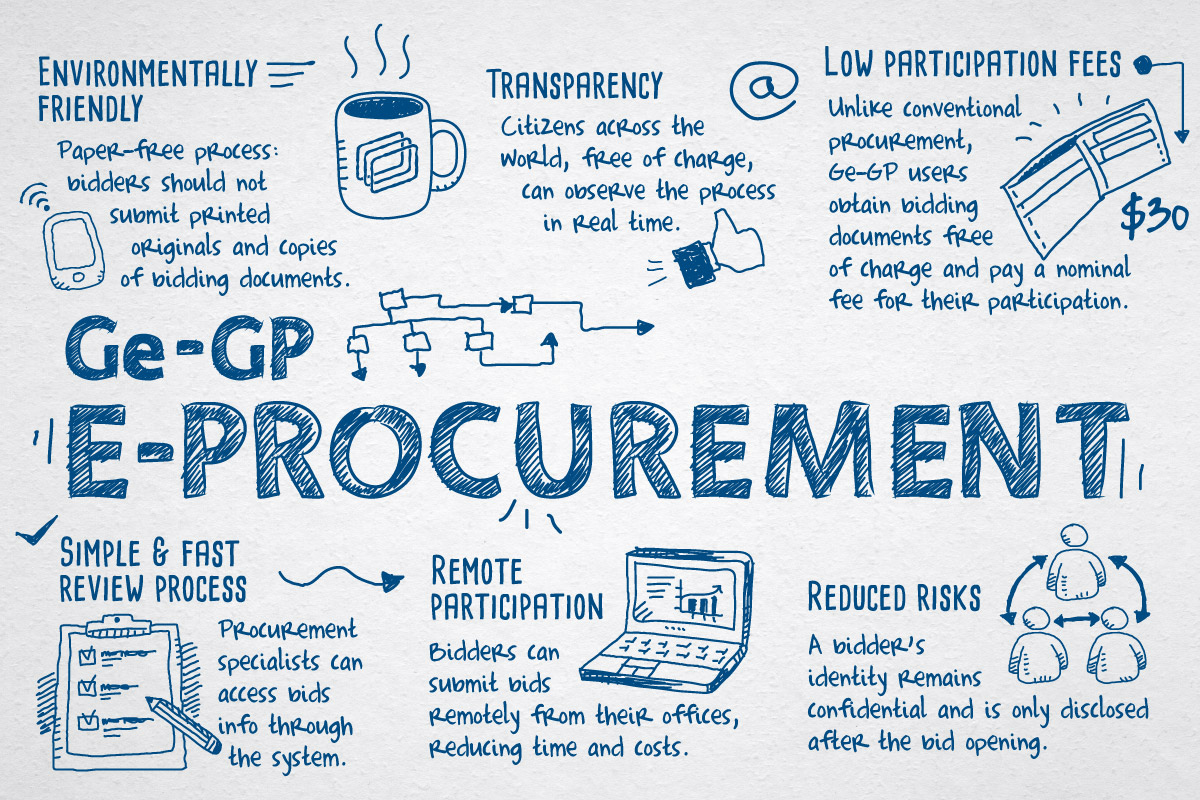

E-procurement in Georgia. Image credit: World Bank Blog

As cyberspace replaces public space due to COVID-19, the growing trend of adapting state functioning to the digital landscape — whether through e-taxation, electronic identity management, or open data to improve service delivery (e-procurement) — has become a top priority. During my time as a Fellow at the Transparency and Accountability Initiative (TAI), e-government projects have emerged in Honduras, Mongolia, and Portugal amid the pandemic.

Among the various e-government tools, e-procurement especially offers funders an opportunity to impact both public coronavirus responses as well as the field of transparency, accountability, and participation.

What is meant by e-procurement?

The European Union defines e-procurement as “the business-to-government tendering and sale of goods, services and works through online platforms.” E-procurement platforms are both marketplaces (where tenders can be announced, bids submitted, suppliers vetted digitally, and contract award notifications posted) and archives where public procurement data can be stored and shared.

Moving processes such as procurement online can enhance government service delivery in 3 ways:

- Digitally automating key steps in the procurement process can make public transactions more ‘auditable’ and reduce the discretionary power of bureaucrats and public officials, which otherwise might breed petty corruption and kickbacks. Procurement is the leading corruption risk in the public sector due to the large volume of money changing hands ($13 trillion worldwide annually). Shadowy contracts with shell companies are a common way of siphoning off money intended for public services—offering procurement through a “transparency portal” displaying timely online publication of key government documents and subjecting tenders and awards to public scrutiny can minimize opacity.

- E-government tools can also foster accountability by facilitating information flows vertically downwards from governments to citizens, vertically upwards (e-government tools are also linked to greater citizen participation in political life), and horizontally between branches of government on online platforms. Effective procurement benefits from all three information flows working effectively.

- Finally, according to OECD findings, this enhanced accountability and more efficient transmission of information engender better utilization of public resources. The European Commission reports that in Italy, e-procurement saved over €4.69 billion in costs in key areas such as healthcare and education. The pandemic makes accelerating efficiency in public service delivery, simplifying processes, and providing savings for government coffers more urgent than ever. Optimizing public spending using digital tools can free up resources for COVID-19 relief funds, macroeconomic stabilization, or paying off national debt.

Of course, e-procurement is no silver bullet for good governance. Expectations for tech-savvy governance projects are often unrealistically high. Implementation costs are often high as well. Complementary legal frameworks and wide buy-in are also essential for sustained change. As Development Gateway writes, governments “implementing new technology rapidly can be notoriously cumbersome, glitchy, and delayed,” meaning e-procurement projects typically take years to complete. Recent case evidence from Bangladesh and Portugal shows that merely introducing instruments of e-government does not eliminate corruption. Instead, interventions should be carefully targeted and should address practices, such as direct awards, that can slip through the cracks. The digital divide is also a major obstacle to the ability of all to participate equally in e-procurement systems and to deliver on the promise of accountability.

Yet, with public coffers under severe strain and the pandemic upsetting usual bureaucratic procedures, this is an opportunity to innovate and build in much-needed savings. Donor funding from public and private sources can help make e-procurement widespread and more affordable. While some governments have made sizeable investments in e-procurement and other e-government technology, funder-encouraged coordinated efforts between civil society and states (such as the partnership between the Ukrainian Ministry of Development and Trade, Transparency International, tech experts, and the private sector to develop the ProZorro e-procurement platform) are in order to establish and improve e-government infrastructure.

COVID-19 has made the argument for e-procurement more compelling. As the pandemic disrupts supply chains and poses a threat to state functioning , digital procurement infrastructure enables governments to better serve their populations’ needs. Development Gateway’s report on emergency procurement amid COVID-19 finds that not only are in-person transactions inadvisable during a pandemic, but that paper-based, non-digitized processes are too slow at a time when rapid procurement is urgently needed. Lessons from the Ebola outbreak suggest bottlenecks in supply chains for essential equipment and services must be addressed to improve resilience against future crises; the data that e-procurement platforms can provide is vital to this effort.

According to the UNDP, the coronavirus has generated new gaps that digital government services must fill and has put a strain on existing services. The states most under strain, those that could benefit greatly from e-procurement and other e-government services, are likely strapped for cash and unable to finance these new initiatives. With assistance from donor finance, e-procurement can fulfill a government’s responsibilities to its citizens and offers an opportunity to support recovery processes, while minimizing bureaucratic costs, at a time when state budgets are stretched thin.

Donors would be well-served to prioritize funding groups that can help create e-government processes, specifically e-procurement, to ‘build back better.’ The Open Contracting Partnership (funded by TAI members Open Society Foundations, Hewlett Foundation, Luminate, and FCDO), which supports e-procurement projects upholding the Open Contracting Data Standard, is a prime example of the promising direction in which momentum can go.

The combination of technical assistance from the Open Contracting Partnership, an Open Government Partnership Action Plan, and World Bank and European Bank of Reconstruction and Development funding in Moldova has yielded positive results. E-procurement was adopted and scaled up to become a full-fledged marketplace in record time, yielding savings of 14% on public tenders.

Similarly, Indonesia (where e-procurement infrastructure was established in 2008 and public procurement data on selection processes are now accessible online) and Argentina (whose platform COMPR.AR funded by the Inter-American Development Bank has been linked to greater savings, supplier participation, and faster procurement cycles) have seen progress in e-procurement following commitments to Open Government Partnership National Action Plans.

Margarita Gomez of the Oxford People in Government Lab believes adopting e-government technology is a means to transform a crisis into an opportunity to build public trust. When well-executed, e-procurement can enable an entire government ecosystem to function more rapidly, cheaply, and effectively when citizens need it most while enhancing transparency, accountability, and participation.