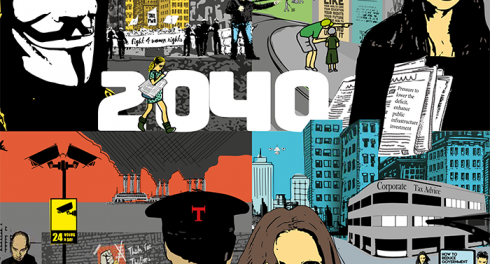

The meeting used a scenario building methodology, which challenged us to imagine the world in 2040. We developed four future scenarios for a fictional country called Thule, named after a legendary island beyond the borders of the known world. A full description of each of the scenarios and a guide to using them for strategic reflection is available here: internationalbudget.org/fiscalfutures.

In debating these scenarios, we identified five critical areas that need more investment if want to increase our chances of achieving the positive scenarios and avoid ending up closer to the negative scenarios. The implication is not that we should throw away our current work priorities, but that we should invest greater effort in these areas because they might constitute a powerful agenda for strengthening fiscal accountability and justice in developing countries around the world.

FIVE AREAS OF UNDERINVESTMENT IN FISCAL JUSTICE WORK

1.) INCORPORATING INCLUSION AND EQUITY

In each of the negative scenarios, a populist or right-wing demagogue creates a vision for public resource management that captures popular disgust with corruption, but ultimately leads to even greater inequality and/or the militarization of society. In each case, the opposition did not have an alternative vision for fiscal governance that effectively addressed inclusion and equity. What was missing was a strong counter-narrative to the dominant economic growth-centered paradigm that explicitly challenges the concentration of wealth and pursues redistributive goals in tax and spending policy. The challenge before us as a field is to develop such a fiscal governance framework, rooted in equity and social rights principles, that can help us advance a new social contract and build powerful, broad constituencies for change.

2.) INTEGRATING REVENUE AND SPENDING WORK

Raising sufficient revenue to meet the challenges of young populations and aging populations is a clear constraint across all the scenarios. All four contexts build up substantial debt by 2040 that threatens to deepen existing income and wealth inequalities and exacerbate citizen alienation. The task for us today is clear: domestic resource mobilization will continue to be a key public finance challenge for many years to come. Without a stronger effort to fight existing power asymmetries, countries are likely to raise these additional resources in ways that further entrench inequalities by imposing significant burdens on current and future low-income communities.

We must meet this challenge by building the organizations, constituencies, and tools needed to turn the international push for domestic resource mobilization into an agenda for raising adequate resources that improve equity rather than entrench inequality. This means developing new strategies for generating informal and formal revenue in rapidly changing economies and expanding civic engagement on these issues. To do this effectively, we need to better link (currently siloed) civil society work on spending, revenue, and debt. For example, work on public expenditure is much more powerful when linked to sources of financing, while work on public revenue animates citizens much more easily when it is connected to public services. We need to invest more in civic engagement in revenue policy at the country level, but there are also compelling opportunities for transnational work, for example in combatting global corporate tax competition.

3.) COMBATING CORPORATE POWER AND CORRUPTION

State capture and unchecked corporate power pervade several of the scenarios, which highlights the urgent need to invest more resources in civic engagement to tackle this scourge. Clearly, the current mechanisms for containing corporate power are not sufficient to address the systemic corporate capture of state institutions around the world. What is needed is a transnational corporate accountability strategy that includes judicial mechanisms with extra-territorial reach and global unitary taxation to ensure transnational corporations pay taxes where they actually do business

Our conversations focused on how to bolster the anti-corruption ecosystem by strengthening public accountability institutions, for example by developing linkages between oversight and investigative bodies. There is also an opportunity to connect fiscal governance/systems knowledge and advocacy to popular anti-corruption movements, with the aim of shifting the focus from reacting to discreet corruption scandals towards promoting systemic efforts to prevent corruption. Lastly, we can do more to identify and engage productively with private sector actors who share these concerns.

4.) GALVANIZING CIVIC ENGAGEMENT AND SUPPORTING BROAD-BASED ORGANIZING

Ultimately, technical fiscal governance approaches that only engage a small section of the population will not be sufficient to challenge poverty and inequality in any meaningful way, especially in countries with a democratic deficit. Each of our worst-case scenarios only tilted towards a better future when a significant portion of the population became engaged in efforts to pursue fiscal justice and accountability. The forces bent on preserving their privilege are just too strong and likely to get even stronger. To effectively counter this trend, it is essential to invest more boldly in creative and long-term efforts to build movements and broad coalitions that create solidarity not centered around tools and approaches, but instead around unifying values and issues that can cut across race, class, and other differences.

Part of this challenge is shifting from an advocacy approach that focuses on supplying public information to identifying and providing specific information in the service of campaigns that people care about and are already involved in. An intriguing idea that emerged in the discussions was the potential to consider campaigning around pure public goods (such as air, climate, and water) to broaden civic engagement and reach the middle classes. Encouraging active fiscal citizenship might also be a core part of a more broad-based approach – one that will require improving people’s fiscal literacy and expanding opportunities for formal and informal engagement in fiscal policy.

5.) BUILDING GOVERNANCE INFRASTRUCTURE FOR FISCAL ACCOUNTABILITY

An important factor separating the favorable and less favorable scenarios was the existence (or non-existence) of strong, independent accountability institutions. This speaks to the importance of legislatures, Supreme Audit Institutions, judicial systems, ombuds offices, domestic human rights commissions, and other similar institutions. Having allied institutions with constitutional responsibilities and formal access to policy processes is indispensable for civil society impact, but these institutions are also vital to protecting systems and standards in the event of executive attacks on civic space and democratic governance akin to what we are witnessing today. Unfortunately, these institutions are too weak to play these roles in too many developing countries, whether because of a lack of independence, inadequate funding, or limited constitutional mandate. There is an urgent need to radically expand efforts to strengthen those institutions that form the core of a fiscal accountability ecosystem.

At the same time, it is important to realize that participatory fiscal practices and institutions are currently not well developed or tested. A new agenda for fiscal governance needs to prioritize experimentation with more participatory forms of governance, both formal and informal, particularly in the budget process.

Prioritizing a governance infrastructure also requires democratizing fiscal data and technologies – a shift that will facilitate a more citizen-defined data infrastructure. Such an agenda must find ways to challenge corporate control of technology and foster a conversation about public good standards for the design, use, and proliferation of technology.

ADAPT OR RISK IRRELEVANCE

The Transparency and Accountability State of the Field Review that we commissioned as the foundation for our scenarios work makes it clear that the fiscal accountability field hit a plateau well before we achieved our vision of matching public money to the just distribution of public resources. Despite significant success over the past 15 years, we cannot afford to be complacent. Further success rests on testing new approaches.

To successfully make the shifts flagged through this process, we will need to evolve our strategies, not just our tactics, and work more politically. Only then will we help ensure that fiscal processes meet the needs of poor and marginalized communities, not just those of the rich and powerful.

First appeared on IBP site