Photo: Johnhain on Pixabay

Almost exactly a year ago, we excitedly blogged about the newly-minted Learning Collaborative, a two-year pilot to test out a model of organizational learning and collaboration among non-governmental practitioners and academics in the transparency, accountability, and participation (TAP) field. Many civil society organizations (CSOs) around the globe aspire to continued learning and building on the resulting lessons; doing it in practice is not always an easy task. In many cases, basic resources, including time, organizational processes, funds, and partners to learn with are scarce.

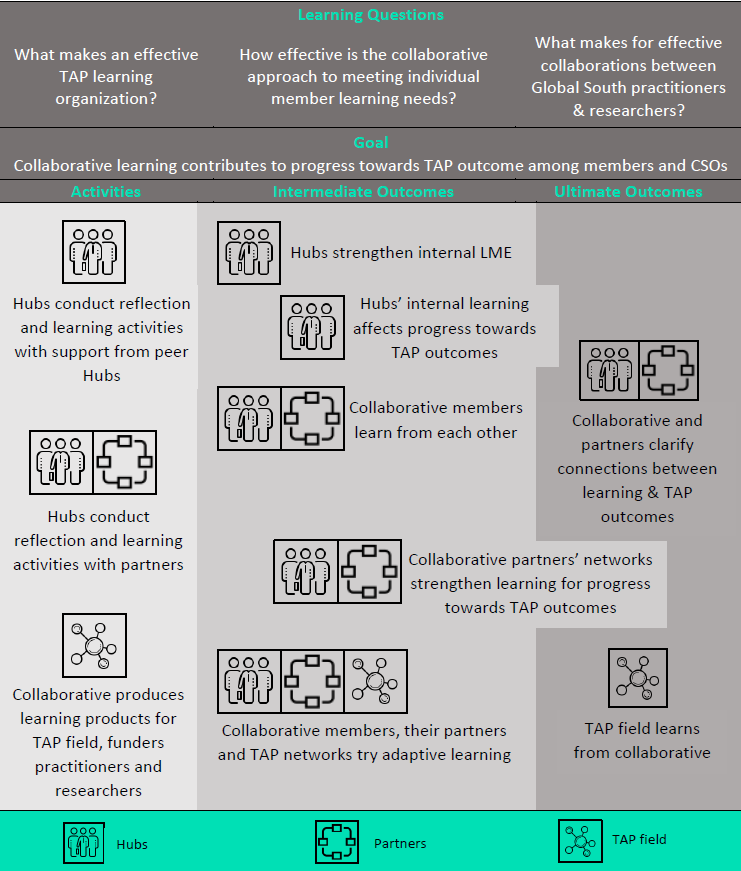

Launched in January 2018 with the support of Ford Foundation and Hewlett Foundation, the Collaborative has three overarching outcomes. The first is to clarify how attention to organizational learning practices can improve transparency, accountability, and participation (TAP) practice, building particularly on the expertise of CSOs working in the global South. The second is to deliver productive learning exchanges targeted to practitioner needs and test the hypothesis that a peer-based, collaborative model enhances learning. And the third is to inform and influence the broader TAP field and philanthropic actors on effective learning approaches.

The Collaborative is composed of four learning Hubs—Centro de Estudios para la Equidad y Gobernanza en los Sistemas de Salud (CEGSS), Center for Law, Justice and Society (Dejusticia), Twaweza East Africa, and Global Integrity. These are established organizations working in the TAP field, already making use of reflective learning approaches in their work. They are supported by resource organizations that promote practitioner-based evidence and learning in the TAP field more broadly: the Accountability Research Center at American University (ARC), MIT Governance Lab (MIT GOV/LAB), and the Transparency and Accountability Initiative (TAI).

What has happened in the first year of the Learning Collaborative? We describe three main processes and related outputs which were necessary to pave the way for the Collaborative to begin functioning as, well, a collaborative.

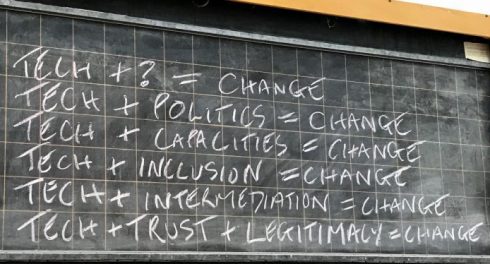

Agreeing not only on a common vision, but the outline of the path to get there. We needed the first half of the year to hammer out a Theory of Change for the collaborative overall, a corresponding results framework, and a joint annual plan. The TOC, in particular, has been essential not only for the common visioning but also for its clear and agreed outcomes. We assessed progress against those outcomes at the end of the first year. From this exercise, we find that the Hubs were able to accelerate their own learning activities in 2018. In some cases, they were also able to accelerate learning within their pre-existing networks. The most challenging component of the Collaborative has been the design of collaborative-level learning efforts and linking with the TAP field.

Photo: Summarized TOC by TAI

Constructing our own learning baselines. In the second half of the year, we conducted a series of peer-led assessments of each of the Hubs’ organizational learning strategies and practices. Although these required significant time and resources, we felt that without these, how would we know whether the members improve their learning practices as a result of being part of the Collaborative? The intensive, in-person visits to the Hubs comprised detailed discussions with a range of staff and covered the following areas: (a) organizational strategizing and setting of goals and theories of change; (b) monitoring practices and use of data; (c) evaluation practices and use of results; (d) staff and organizational strengths (or needs) in engaging meaningfully with MEL; (e) learning and reflection opportunities within each organization; and (f) identifying areas for potential links between Hubs for learning support as well as collaborative research. These processes – and the ensuing outputs – were reported as very useful by the Hubs. In 2019, we aim to describe the approach in a methodical way so that a wider set of actors can use it.

Making the total greater than the sum of our parts: designing joint learning projects. It was clear early on that, given the active and committed nature of the participating Hubs, the organizations would have no trouble using the resources provided through the Collaborative to strengthen their own learning practices, as well as the learning practices within the organizations’ pre-established networks. But we all knew that these activities didn’t need a collaborative structure. The real “proof of the pudding” of the Collaborative was whether we could craft joint learning projects according to a demanding list of characteristics. These projects were to span two or more of the participating Hubs and meaningfully draw upon the academic support partners, be genuinely productive for the Hubs (that is, arise from a real, felt need whether in learning or TAP content), and correspond to a gap in knowledge or practice in the wider TAP field, so that the lessons would be meaningful beyond the immediate participants. We indeed closed 2018 with outlines of three such projects on the following topics: experiences and lessons of working with allies in government in the context of closing civil society space; the use and effectiveness of strategic litigation in TAP; and developing learning-centered, adaptive MEL methods for frontline or grassroots organizations. These are the focus of our joint efforts in 2019.

Last but not least, we are observing, tracking, and assessing the overall Collaborative experiment. Together with the participating organizations, we regularly reflect on our own practice and implementation of this model. Does it deepen organizational learning and improve overall practice? Does it generate new and interesting insights and results? What seems to be working and how, and what doesn’t seem to be and why? Given the interest in supporting effective learning practice among practitioners in the TAP field, this Collaborative experiment may have much to teach us. Look out for our initial musings on these questions in a subsequent blog post.

Varja Lipovsek is a research scientist at the MIT Governance Lab (MIT GOV/LAB) and Karen Hussman from Dejusticia.