This week the world’s tax and domestic resource mobilisation (DRM) community are gathered in Berlin for the ATI/ITC Tax and Development Conference, organised by the Addis Tax Initiative and the International Tax Compact.

With donors increasingly looking to move DRM programming beyond mere technical support to governments, one issue expected to get attention this year is the role of civil society in tax reforms.

However, there is a risk that donor efforts to support civil society’s engagement in tax can be somewhat unimaginative. Echoing broader development practice, there can be an impulse among donors to stay on comfortable ground, and assume that all that civil society organisations need be effective advocates for DRM is technical training and capacity building.

There are clear gaps in civil society’s technical capacity to engage in and influence tax debates and policymaking processes. But this approach skirts around questions that are more fundamental: why would civil society organisations want to engage in tax issues to begin with? And is it simply a lack of technical skills that constrain their engagement and influence?

These are some of the issues that my colleagues Stephanie Sweet, Alina Rocha Menocal and I seek to address in an upcoming report that the Transparency and Accountability Initiative commissioned from the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). Through interviews with civil society working on domestic tax issues, donors, and governments, our research provides snapshots on the state of domestic civil society engagement in tax reform in eight countries across Africa, Asia, and North and Central America. Our study also teases out implications for grounding donor support in the contextual realities that shape civil society’s interests, influence and capacity.

Among the many emerging findings from this research, one thing is clear: the nature of the challenge of how civil society organisations (CSOs) engage in tax, why, and to what effect is above all political.

The most notable feature of CSOs that have proven influential in the tax space across the eight cases we analysed was that they all tend to work in politically savvy ways. They often combine analysis with advocacy; public mobilisation with behind-the-scenes structured engagement; and built coalitions for reform across government and civil society. These are the kinds of soft skills that technical training alone cannot provide.

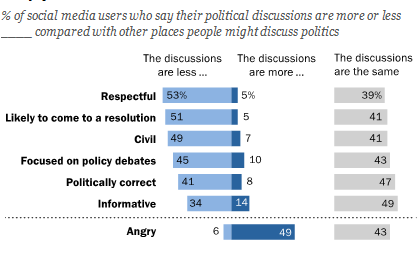

Working on tax is difficult for CSOs, especially when public trust in government is low. It’s easier to mobilise public opposition to unpopular taxes than to campaign to increase domestic resource mobilisation through taxation. Rather than assume that CSOs naturally want to work on a progressive agenda for tax reform, donors would do well to start by deepening their understanding of where the pressures to reform tax systems are coming from, and where this aligns with the interests of different civil society actors. The CSOs we spoke with as part of this research, disproportionately favoured work on international and extractives taxation and excise duties (as opposed to income taxation for example).

Existing discussions on civil society and tax in international development circles have focused on the potential role of CSOs as educators: communicating tax rights and obligations, and making links with expenditures (both to increase tax compliance and spur accountability demands). However, most of the domestic CSOs interviewed in this research prioritised engagement in national tax policy debates over tax education. To what extent donor support can, and should, spur more tax education work from civil society is worth testing.

A tax ecosystem

So what does this mean for donors? One implication is that they need to prioritise working in more politically savvy ways. How can they do so?

The Addis Tax Initiative (ATI) commits members to increasing domestic revenues and improving ‘the fairness, transparency, efficiency and effectiveness’ of tax systems. But how different states and societies work towards achieving these goals will be part of a process of contestation and bargaining among an ecosystem that includes diverse actors with diverse interests.

We encourage donors to engage with this ecosystem and develop a more holistic approach to support DRM efforts. This includes working not only with governments, but also with other actors that can advocate, analyse and build awareness on tax. But we also encourage donors to take the political nature of ongoing contestation within and between stakeholders in state and society seriously. Improvements in DRM efforts will not emerge from simply building the technical capacity of these different actors.

As a result, as we argue in our report, which will be launched in July, donors need to think more strategically about who they support in a given context, how, and why, in ways that may influence the outcomes of these ongoing contestations.

Sam Sharp is a Research Officer at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).