Since 2009, Chile’s Ciudadano Inteligente have been creating digital solutions for basic problems of citizenship—like finding good voter guides or tracking the voting histories of public officials.

With their new Poplus program—part-community outreach, part-software development—Ciudadano Inteligente are expanding their leadership in Latin America’s open government movement, widening their scope from tools for individuals to tools that can help other civic groups promote transparency and accountability.

This week, early adopters and potential users of the Poplus software are gathering in Santiago with project creators from Ciudadano Inteligente and the UK’s mySociety.

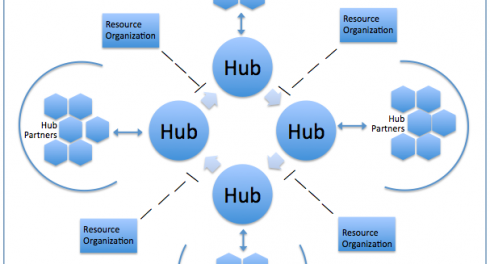

NGOs face a high startup cost for any new tool, due to limited resources and, often, little tech experience. Poplus is designed to “reduce the barriers to entry for civic groups when they start web projects,” says Pedro Daire, the group’s lead technologist and a regular participant in the TABridge network. The system is built on “basic components that have just one task,” he says, such as a document library or a petition form. Each component “has one objective that has to be accomplished in a very generic way, and this can be used to build something in just a day or two” for each user organization.

So far, the functions in the Poplus suite include posting public transcripts and statements, mapping jurisdictional boundaries, contacting or listing details on public officials, and filing and displaying legislative and other documents. Each tool is designed to be freestanding but is also interoperable with the others if required.

“We are investing a lot of time to deploy the tool in different contexts,” Daire says, with Latin American projects underway in Argentina, Paraguay and Venezuela, among others, and African tools being developed in Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa and Zimbabwe in partnership with mySociety.

Tom Steinberg, mySociety’s founder, says the components-based Poplus approach can help groups avoid “spending time and money to solve the same problems again and again in a field that isn’t really rich enough to be able to afford much waste.” mySociety, who created breakthrough citizen-powered sites FixMyStreet and WhatDoTheyKnow, are longtime allies of Ciudadano Inteligente and helped to inspire the Chilean group’s first online experiments in 2009 and 2010.

mySociety also comes to the project with experience turning outward to share their knowledge and tools: The FixMyStreet platform is packaged for replication and re-use by any interested group or jurisdiction. And their Freedom of Information tools are the basis for Alavateli, a web-based FOI request system adopted in projects from Europe to Africa to Latin America.

Daire says that past attempts by Ciudadano Inteligente to adapt their tools for new uses were prohibitively difficult, with each country’s “singularities” creating a burden of customization. Peru, for instance, has one legislative body, not two, which proved to be a huge obstacle in adapting the code originally used to monitor Chile’s bicameral system.

To account for customization challenges, Steinberg says Poplus was conceived as a “halfway house between endless repeated labor and a single monolithic platform … small, loosely joined pieces that organizations could pick up” as and when they need.

By balancing reusability and flexibility in the Poplus software, the creators of the toolkit are operating according to a fundamental value within the #TABridge network, the paramount importance of user needs—and staff needs—when designing advocacy tools.

Most technology demands customization, but by streamlining the basic tools, and highlighting customization issues from the start, the Poplus developers have written something even more important into their code: the chance for self-reliance. Steinberg says “we’re trying to change the landscape so that groups don’t have to have such amazing tech skills.” A lower barrier for getting started, he says, “makes the formation of successful teams a more realistic proposition.”

The participants in the Poplus conference are getting an opportunity not only to acclimate to the brand-new tools in live trainings, but also to co-design future features and add their voices to a shared process.

In addition to building team skills and stronger feedback loops, Poplus can also shift an NGO’s fundraising outlook, says Daire. Too often, organizations pitching tech projects to donors can say little more than, “we have this idea,” he explains. With the simple starting point Poplus provides, he says a group can approach donors “with something. It’s very different when you approach donors and say, ‘We have this tool already up, with information in it.’ It’s much easier to scale a project than to start a project.”

Daire has the chance to test these questions firsthand. He recently became the first director of Ciudadano Inteligente’s LatAm Labs, a new division that consolidates the technology investments he has helped to champion. He calls the organization’s new direction “an evolution toward becoming a service NGO,” adding, with a technologist’s caution, “somehow.”

The Poplus project may represent an evolution in how transparency groups bridge gaps between mission and technology capacity, not just for themselves but for their peers around the world. A group may look to tools to create new approaches, but over time it‘s the team, not the tools, that can drive lasting change.

To join the growing community working on Poplus, follow #PoplusCon on Twitter this week, and watch for news and new tools at Poplus.org.