Photo Credit: Accountability Lab

An influx of international aid in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has everyone – international donors, media, and civil society – raising the alarm about increased corruption risks. The World Bank alone has committed to providing up to $160 billion for pandemic relief in developing countries, of which $55 billion will be for Africa. And rightly so – corruption within COVID-19 responses has been rampant – think of South Africa, for example, or Zimbabwe, or the Democratic Republic of the Congo. There is little doubt that corruption has worsened during the pandemic, and tracking billions of dollars of aid money is next to impossible.

Over the last six months, Accountability Lab Liberia – with support from UNDP and the Skoll Foundation – carried out a campaign to “follow the money” provided to support the Government of Liberia’s efforts to fight the pandemic. The aim was to track $155m of international aid channeled through different government agencies, but our volunteers who were trained to collect data from the ground, were able to report back on only 27% of the targeted amount.

Some of the challenges and lessons learned are not unique to Liberia, and demonstrate larger problems when civil society tries to make governments accountable.

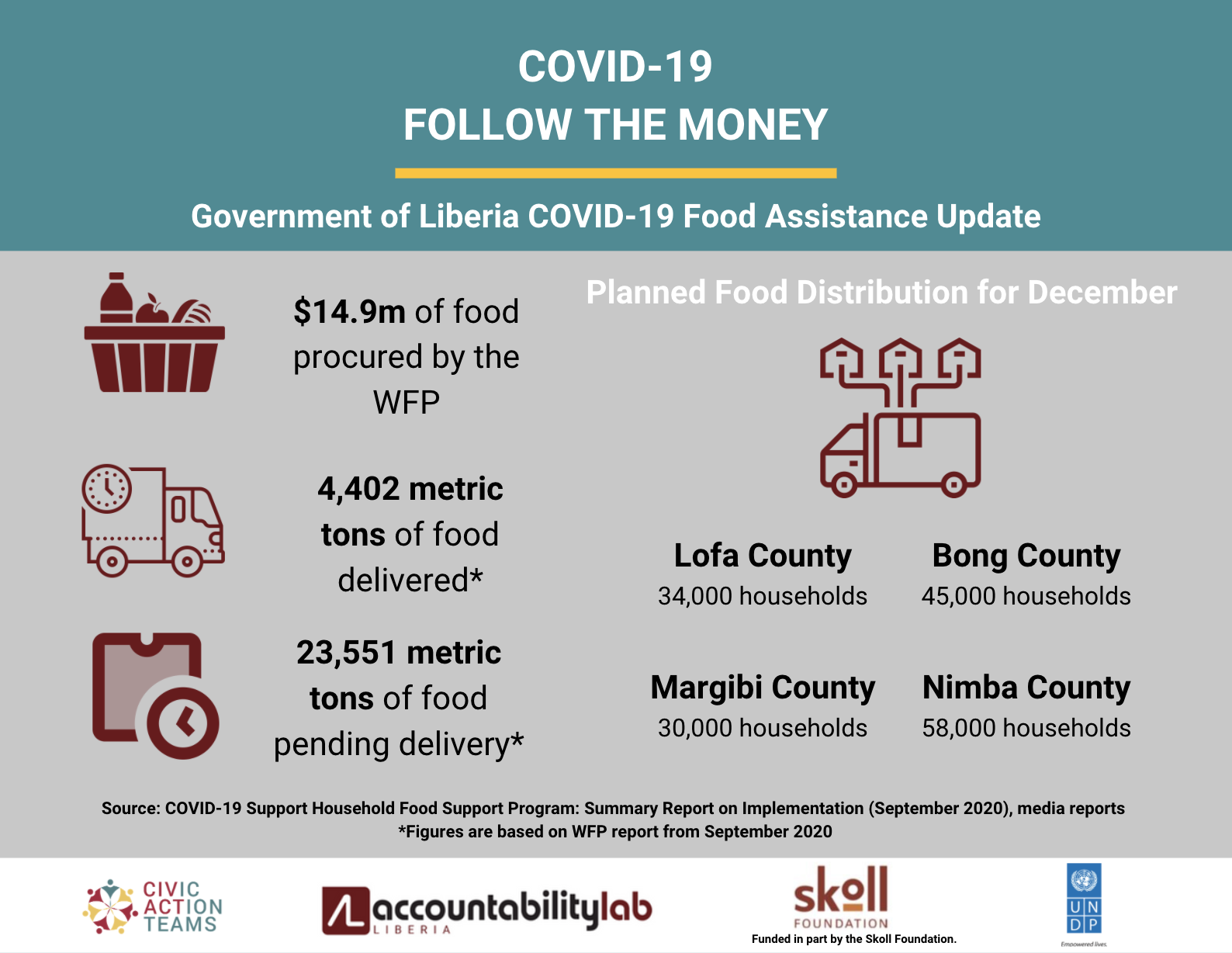

First, we found that simply tracking funds in real-time is almost impossible and even more so during a crisis when lots of decisions are being made quickly, and funds are being disbursed at different levels of government. In Liberia, the COVID-19 support funds were directly transferred by the central government to the counties. For its food assistance program, the government channeled funds to the World Food Programme (WFP), which in turn used three different partners to enumerate households, register them, and distribute food items. Other committed funding were repurposed from existing projects – with systems that were often highly opaque.

Working with multiple stakeholders means governments have to get better at ensuring transparency of data around spending even before crises, so the right systems are in place to ensure probity when emergencies begin. Donors have made efforts to do so through the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), for example, but compliance is low, and in any case, internet access in places like Liberia can be limited, preventing access to this data. Governments too need to create and – where they already exist – use and update centralized mechanisms to make data open and accessible to keep the public informed.

Second, and relatedly, simply setting up online dashboards is not always the solution – the government’s Liberia Project Dashboard lists some of the funds allocated for COVID-19, but there are no other public documents or reports showing how the funds were used and whether they reached the targeted population- so there is some degree of transparency but without accountability. Moreover, detailed reports from the county governments and the WFP on COVID-19 support funds and food assistance were sent to the respective government agencies and political representatives but were not made publicly available. As highlighted in this study, the quality of the information that is made available is what really matters. Simply dumping figures and charts on a website does not necessarily ensure budget transparency. The major challenge here is the government’s lack of ownership on the openness agenda.This is one of the areas we are working on with the Liberian government through the Open Government Partnership (OGP).

It is important for the government to incorporate ‘meaningful openness’ into the entire budget planning, disbursement and reporting period. As a start, the Government of Liberia could allocate human and financial resources to ensure there is a designated staffer collecting and updating budget information. Coordinating with various government agencies will also require buy-in from the highest level of government – the President’s Office, for instance – which could delegate a key decision-maker to take charge of budget transparency and ensure compliance from all agencies. And, while the systems and tools are being developed, the government can ensure that other means of information dissemination are fully utilized– such as community radio shows in local dialects and community town hall meetings.

Third, governments and donors can be wary of those working on accountability – this means even with the right contacts and relationships within the government and international partners, we were often unable to engage and gather information. There have been reports of governments across the globe shrinking civic spaces during the pandemic. This happens for a variety of reasons – the government may see civil society as a threat or disruptor at a time when public opinion may not be in their favor. Governments are also reluctant to admit their shortcomings in terms of managing the pandemic and handling relief efforts. This may be true for international partners as well – gathering information from donors was equally difficult for our team. In Liberia, government inefficiency in distributing food assistance to vulnerable populations was highlighted in civil society organizations’ media and independent reports.

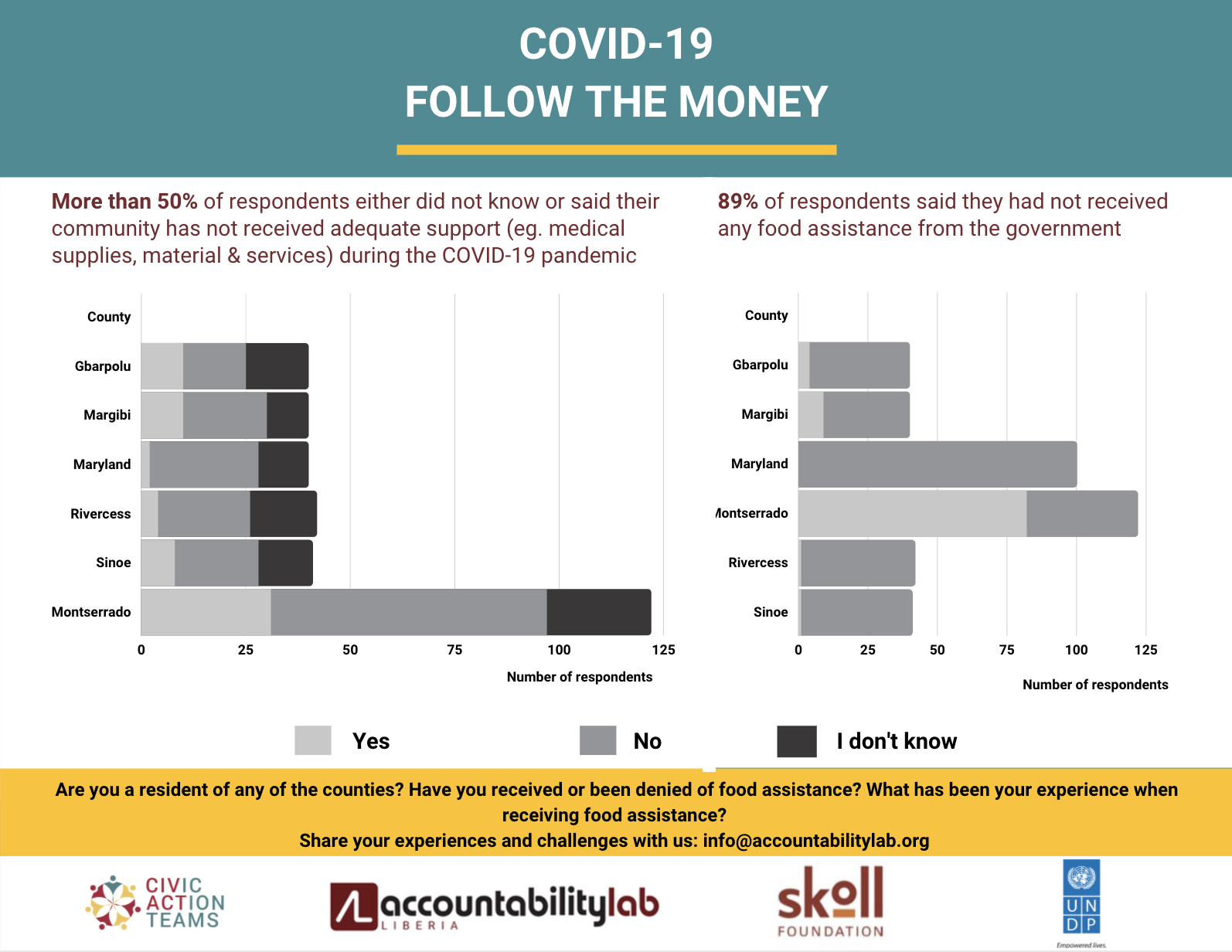

In a perception survey we carried out in 6 Liberian counties, 89% of respondents interviewed said they had not received any food assistance from the government. It is crucial for all those involved in managing relief efforts to provide regular updates to build public trust. This is especially important when plans change or are ineffective – clear and timely communication can help manage public expectations. Government agencies and international partners can, as a start, send out weekly press releases or daily media briefings stating the timeline and targets for their relief activities.

Fourth, there was a lack of reliable grievance redress mechanisms. Most of the time, we found that there was no way for people to register complaints related to COVID-19 relief efforts. People who were left out of the food assistance program complained they had reached out to those responsible for food distribution, but they did not get any response. Promoting existing government mechanisms could be a way to address this, and increase civic engagement and improve government accountability. For instance, Liberians should be able to access budget information by talking to their district representative or by joining County Council town hall meetings and public hearings; or by writing to their County Superintendent, Mayor or Commissioner. Through our bulletins, we aimed to make people aware of these different government mechanisms already in place at the local levels and encourage engagement with them. There are also examples of how other countries are doing this well during COVID-19 – which could be replicated even in a low-resource environment. In Odisha – eastern India, for example, the state government has set up dedicated call centers to address public queries about COVID-19; and an online Grievance Redressal Portal, even with minimal resources.

Finally, despite the challenges, CSOs have an essential role to play in filling information gaps and closing the feedback loop. The COVID-19 response and recovery is not over, and funds will continue to be poured into countries like Liberia. In the coming months, reports and stories on how these funds were misused will pop up. CSOs still need to be vigilant, seek information, and push for accountability, despite the challenges. Programs like the DCDJ program in Cote D’Ivoire – which has been supporting young people to collect and use data around healthcare issues – need to be scaled up. We can also learn from others like Compras COVID in Chile, which have found creative ways to popularize pandemic-related data. Liberia is finalizing its new OGP Action Plan – and this also provides a mechanism through which civil society can work collaboratively with the government at all levels to achieve key reforms related to the COVID-19 response. As vaccines become available, we must also ensure that local CSOs in countries like Liberia have the data, tools, and support they need to monitor donors and the government to ensure a fair, effective immunization process.

Nyema Richards is the Learning Manager at Accountability Lab Liberia. Sanjeeta Pant is a Programs and Learning Manager at Accountability Lab. Follow the Lab on Twitter @accountlab.