This is the second of two blogs that discusses TAI’s main evaluation insights and what the collaborative is doing to act on those learnings. Part one of this blog covered what motivated TAI to commission an external evaluation and insights from the process. You can read a summary of the main evaluation findings and learnings in TAI’s evaluation brief.

Learning-driven evaluation prioritizes asking the “big” questions that really matter to an organization. But this involves a bit of a leap of faith because you must be prepared to act on the resulting answers, even those that you hoped not to hear.

We identified evidence of many positive practices and achievements for the Secretariat and funder members, which are detailed in the TAI’s evaluation brief. I also highlight here key insights around gaps uncovered. We found these data points to provide the clearest signals for adaptation and, therefore, the greatest learning value to our future collective work.

What Did We Learn?

Value-Add for Members

Value-Add for Members

TAI was found to be fulfilling our funder-serving orientation, and 86% of surveyed members agree or strongly agree that they benefit from their participation with TAI.

Our members said:

“TAI creates space to gather and cultivate information, ask questions and learn in a more complex and nuanced way.”

“We have been exposed to ideas that have led to [new] grant making.”

“If we wanted to get to similar outcomes [without TAI], we’d have to commission a lot more research independently to look at trends in the field and scope opportunities for investment.”

Our members value TAI most as a:

- Platform for learning, coordination, and risk sharing with trusted peers.

- Source to inform smarter and more efficient individual funder results.

- Bridge to the transparency, participation, and accountability field.

Theory of Change

- TAI’s outcomes are inspiring signals of intention but are not consistently or adequately timebound relative to our strategy period or to member funding commitments. This hinders TAI’s ability to assess incremental progress and to demonstrate value to members.

- TAI faces tension between outcomes framed as a practitioner seeking field-level change and the operational model and activities of a funder collaborative. In practice, this leads to inefficiencies for the Secretariat and misaligned expectations among members.

- TAI’s theory of change links member practice to impact on grantee organization experience and behaviours, but this framing belies the intention of learning from and with grantee organizations and other funders. It also represented a logical leap that our member-serving work would yield direct and systematic benefits to individual grantee organizations.

Strategic Framework

- TAI’s thematic pillars (data use for accountability, taxation and tax governance, and strengthening civic space) were too broad to easily spark concrete collective initiatives and too rigid to enable TAI to evolve with member strategic shifts and new contextual needs or opportunities.

- Along with these thematic areas, learning for improved grantmaking was a stand-alone pillar. This positioning aligned with our collective commitment to learning, but it unintentionally siloed TAI’s learning work relative to the thematic pillars.

- One of several focus areas within TAI’s learning work featured improved member grantmaking practices. Amidst many other strategic goals, attention to this area was limited. And member interests transcended grantmaking to a broader range of grantmaker approaches and tools.

Collective Purpose & Operations

- Evaluation evidence affirmed TAI’s 2016 pivot from a field-facing to a member-serving approach; this is a comparative organizational advantage and generates a range of benefits for funder members.

- Our shared understanding of TAI’s collective purpose has become fuzzy across broad thematic pillars, any one of which could serve as the singular focus of a collaborative. TAI’s experience and value-add for members are anchored in connecting people and supporting learning towards action. In practice, this was lost amidst the effort to sustain different ways of working for each of the four strategic thematic pillars.

- We found an unhelpful lack of clarity around governance policies and processes related to institutional membership and member staff and Secretariat roles and responsibilities. Some of the strategic and purpose findings above likely contributed to this operational gap.

What Next for TAI?

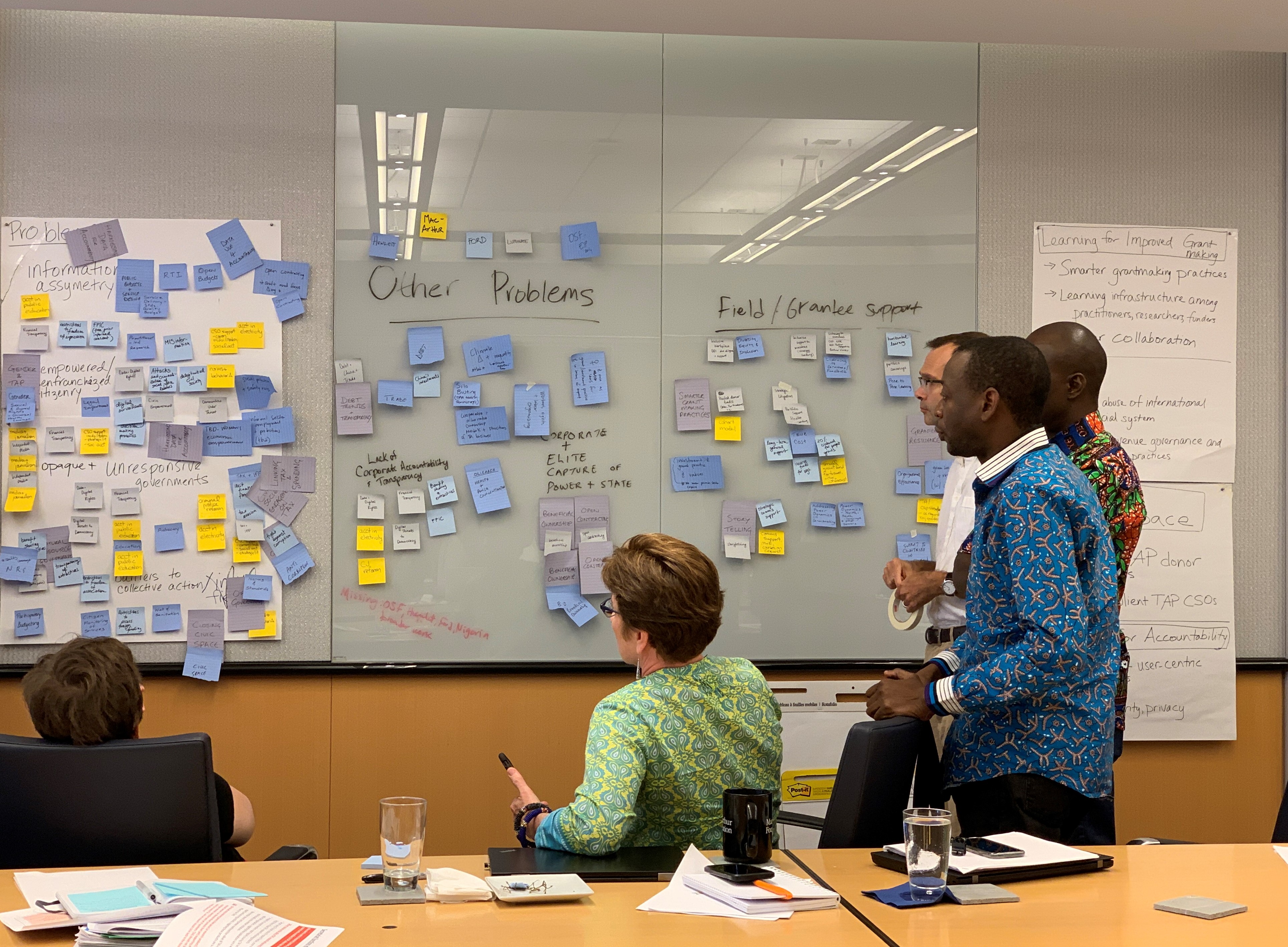

After (briefly!) pausing to interpret and reflect on these findings, TAI took several steps to use this evaluation to strengthen our work. This included forming a member working group to revise TAI’s theory of change; drawing on an organizational health fund grant from OSF to refine our membership terms of reference, and dedicating time at our member 2020 retreat to build our collective strategy. Stay tuned for TAI’s 2020-2024 strategy!

After (briefly!) pausing to interpret and reflect on these findings, TAI took several steps to use this evaluation to strengthen our work. This included forming a member working group to revise TAI’s theory of change; drawing on an organizational health fund grant from OSF to refine our membership terms of reference, and dedicating time at our member 2020 retreat to build our collective strategy. Stay tuned for TAI’s 2020-2024 strategy!

| What TAI Learned | What TAI Will Do |

| Theory of Change | Revise theory of change around our organizational perspective as a funder collaborative, rather than a programmatic field actor. |

| Update TAI’s monitoring, evaluation, and learning system and practices in service of the revised theory of change and key stakeholders we seek to engage with and learn from. | |

| Strategic Framework | Eliminate thematic pillars in the strategy and adopt a process to define member-driven, time-bound collective initiatives. |

| Balance our level of intention and focus between what members fund thematically and how members use financial and non-financial tools and approaches. | |

| Purpose & Operations | Convert learning from a stand-alone pillar to a core function and reinforce TAI as a member-serving platform for learning and collaborative action. |

| Seek member input to refresh member terms of reference; update institutional membership criteria and processes. |