In the second part of this blog (read the first part here), our Monitoring and Evaluation Fellow, Mavra Zehra identifies ways grantee organizations can influence funder grantmaking practices.

Photo credit: Gordon Fischer Law Firm

In philanthropic practices, top-down decision-making is increasingly viewed with suspicion. Funders are increasing efforts to engage grantees with a view to aligning funder practices to recipient needs. Yet how might grantee influence play out in practice? To what extent can a grantee influence a funder to adjust its grantmaking practices? My own experience working in the non-profit sector indicates the answer is typically very little, but there exists evidence that proves otherwise.

Here, I have identified four major ways grantees can influence funders. I reference examples from the United States where the literature is deepest, but I welcome suggestions of cases from other geographies that reinforce (or challenge) these suggested pathways to influence.

• Field Knowledge: Perhaps the easiest starting point is the value-addition provided by grantees to a funder’s field knowledge. Funders typically have a broad perspective as they look at multiple geographies while the grantees offer experience and insights drawn from their fieldwork and the communities they are working for and with directly. Grantee reports and evidence generated become important assets for funders who are always motivated to know “what works” (and what does not). Often grantee findings inform bigger picture retrospectives / academic evidence reviews that funders might commission.

Constructive interactions with grantees may also help flag concerns regarding the relevance of the funder’s goals and whether the funder’s programming strategies are sufficiently informed by the evidence on ground. Donors typically have their own strategic frame for engagement, but, working within that frame, a smart grantee can help assure that funding decisions retain relevance for emergent priorities. For example when the Wallace Foundation began funding Prince George’s County Public Schools, the relationship helped them gain a new appreciation of the importance of school principals in tackling systemic problems. This spurred the Foundation to fund new learning questions around who leads the supervision of principals.

• Field Expansion: In some cases, grantee work may suggest opportunities for replication at another scale or in new places that help to expand the field of funded programming. In addition, a grantee has the potential to make the foundation conceptualize its institutional roles beyond traditional roles and responsibilities. When a funder introduces its grantee to other thought leaders in the field and/or provides mentorship advice, it not only invests in the grantee but also in the broader field; making the grantee’s mission easier to achieve. Yet this dynamic works both ways. A grantee can also offer similar benefits to a funder i.e create prospective partnerships by introducing them to other individuals and organizations in the field. For instance in 2008, the American Express (AmEx) partnered with the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL) to focus on creating a Leadership Academy for emerging leaders. With its preexisting experience in professional development, CCL had well established networks and was able to facilitate AmEx’s introduction to other organizations that led to new funding for those groups.

• Influencing Other Foundations: It is the goal of many funders to influence other foundations to advance their advocacy role or campaign efforts. A funder’s partnership with its grantee can yield successful outcomes which create powerful examples to inspire other donors to step into the space. This need not be confined to funding for specific thematic areas, but can extend to the form of funding. For example, in 2016, when the Weingart Foundation offered unrestricted support to MOMS Orange County, the scale of the grantee’s operations and that of its impact went up significantly. That clearer connection between unrestricted support and improved programmatic outcomes, touted by funder and grantee alike, was able to inspire other funders to also shift to providing core support.

• Strengthening Communication Protocols: Grantees have often brought up a desire for clear communication from funders, especially when it comes to relaying information on important programmatic changes. Some foundations have managed to turn such feedback conversations into learning moments and have encouraged their programs officers to strengthen their communications efforts with the grantees for a more transparent and accurate communication of the foundation’s strategic shifts. For example, when partnering with Communities in Schools (CIS), the staff at the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation (EMCF) gained a clearer understanding of the importance of frequent communication and the challenges of network management. This led to some changes in foundation practices and in turn better support to all of its grantees through enhanced communication.

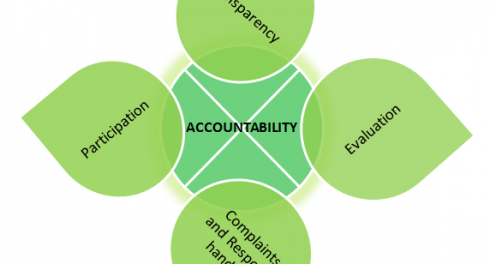

These modes of grantee influence gain their currency through the nature of a long term relationship and are more informal nature. However, more and more funders are asking for structured grantee feedback, often through formal mechanisms like the Grantee Perception Reports. In my concluding post, I will explore the incumbency on donors to act on such feedback and consider the role of intermediaries, such as Transparency and Accountability Initiative, in helping to influence funders towards greater impact.